Questions, legal challenge delay early learning center

By Dan Whisenhunt, Zoe Seiler, and Jim Bass, Decaturish

DECATUR, Ga. – Decatur’s new Early Childhood Learning Center on Electric Avenue faces an uncertain future as the district, parents and state legislators debate the project’s price and how City Schools of Decatur is paying for it.

CSD has postponed the groundbreaking ceremony for the $23 million center while a judge considers whether to validate the bond that would finance the project. The district did not provide an official reason for the delay.

“City Schools of Decatur will not hold a groundbreaking ceremony for the new ECLC this month,” a district spokesperson said. “The ceremony has been postponed until a new date is finalized.”

District officials have not budged on the project and appear determined to see it through. They have said the site’s proximity to the Decatur Housing Authority would help close achievement gaps. The property is located at 346 W. Trinity Place.

School Board Member Hans Utz said during a recent school board retreat that most in the community support the ECLC project.

“As I have had conversations in the community, I've become more and more convinced that it is a minority, a loud but angry minority, opposed to it,” Utz said. “The vast majority of parents that I've had conversations with are actually quite supportive of the ECLC.”

While the project has been under discussion in some form since 2017, opposition has grown since the district began pursuing it in earnest last year. Opponents question the way the district is borrowing money for it.

CSD has an agreement with the city’s Public Facilities Authority to issue the bond, which does not require voter approval in a referendum. The school district is seeking $52 million in bonds and plans to repay the bond over 30 years using sales tax revenue at an interest rate not exceeding 6 percent.

The money will primarily be used to pay for the ECLC and to go toward three other planned Decatur High School projects – a black box theater, an auxiliary gym, and transforming the Frasier Center for Career, Technical, and Agricultural Education classrooms and labs.

A group of residents is challenging that arrangement in court, asking a judge not to validate the bond. The validation makes the bond easier to sell and can lower interest costs. As of Dec. 5, a judge has not issued a ruling. Parents opposed to the validation recently formed the Together for Decatur Schools advocacy group. A spokesperson said they support early learning, but question how the school district has pursued this project.

"Together for Decatur unequivocally supports early education, and we believe that incurring $23 million in debt requires a public vote,” a spokesperson for Together for Decatur said. “By using the PFA to bypass a General Obligation bond, the board is avoiding input from the taxpayers who will pay the bill.”

Legislators befuddled

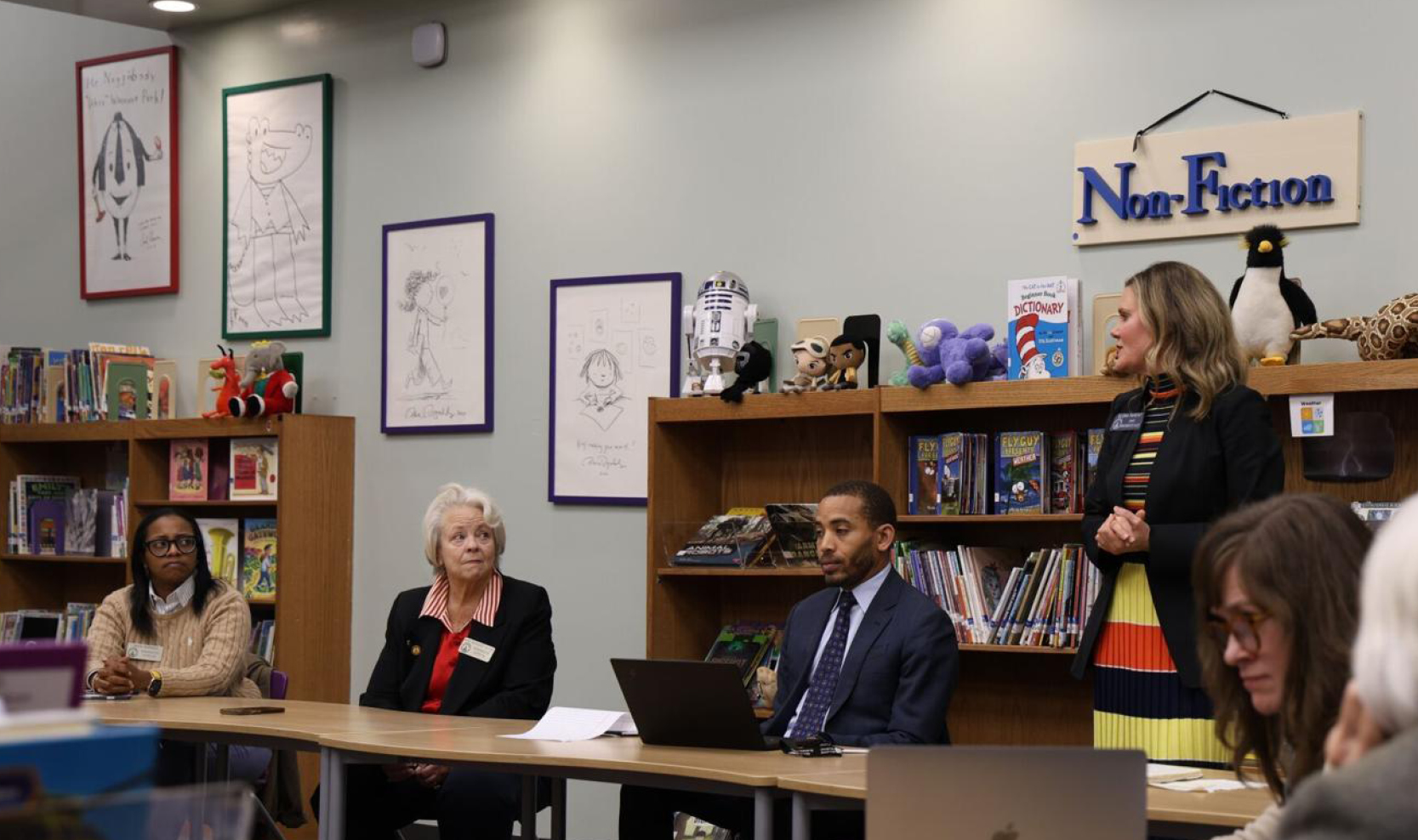

State legislators are questioning the funding mechanism. Legislators, including state Sen. Elena Parent (D - Senate District 44) and state Rep. Mary Margaret Oliver (D - Decatur), fielded questions about the district’s plan to borrow through the PFA during a town hall on Dec. 2.

The Public Facilities Authority’s enabling legislation, sponsored by Parent, authorizes the authority to borrow on behalf of the city’s schools. Oliver thought the PFA was created so the city could buy the United Methodist Children’s Home property in 2017, which has since been renamed Legacy Park.

“I was told it would only be used for Legacy Park,” Oliver said during the town hall. “That's what I was told. And that has turned out not to be true. I've said that to the school board directly.”

Parent said the delegation did not anticipate the PFA would be used for something like the learning center. When asked why the legislation she sponsored allows for it, she said she was not certain, but thinks it was based on similar “model” legislation with the same language. She suggested revisiting the law that created the PFA.

“I feel safe saying that there's some befuddlement among a lot of elected officials in Decatur over some of the decisions being made because they haven’t really been adequately explained to the public, and that causes concern,” Parent said.

Parent recently met with Superintendent Gyimah Whitaker and Chief Operations Officer Jarvis Adams about a potential lease for the SoulShine day care that has just become available. It is within walking distance of Decatur High School and can accommodate 184 students, exceeding the proposed ECLC's capacity of 150 students.

“The whole complex is for sale and/or rent, and it would check a lot of the boxes immediately that the school system's looking for with the new ECLC,” Parent said.

A school district spokesperson said the district is aware that the SoulShine space is on the market, but the plan to build a new ECLC remains unchanged.

“CSD has and continues to receive options for the new Early Childhood Learning Center,” the spokesperson said. “However, the Board of Education had determined and communicated its plans to the public, including the location.”

Parents dig deeper

Two CSD parents published an editorial questioning how the district arrived at its construction estimates.

Patrick and Akila McConnell published an editorial in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, which was also provided to Decaturish, questioning the analysis supporting the need for the day care and how the board arrived at the $23 million estimate.

A CSD spokesperson declined to comment on their conclusions, citing the pending litigation about the bond. During his testimony at the second bond validation hearing, Adams said City Schools of Decatur has an achievement gap.

“The best way to address the achievement gap is early on, and when we look at the demographics of where the achievement gap is coming from, a lot of it is out of the Housing Authority,” Adams said. “So having the opportunity to really address the achievement gap before kindergarten is a huge undertaking, but it's really the right work in education.”

The McConnells’ analysis questions the data supporting the district’s contention that the center must be adjacent to Decatur Housing Authority properties.

“Through our records request, we obtained the raw survey data used as a data point to support these claims,” McConnells wrote. “CSD surveyed 100 respondents, 30 percent of whom are located at DHA. Of those, only two reported needing day care and lacking transportation, or just 2 percent.”

They scrutinized whether CSD received the best price for the ECLC construction. They said CSD requested proposals for a Construction Manager at Risk in February of this year. Under a CMAR, the contract usually includes a guaranteed maximum price.

CSD set the price at $23 million and approved a $40,000 preconstruction contract with Parrish Construction Group in April. They learned that the contract with Parrish does not have a guaranteed maximum price or a price breakdown. CSD’s evaluation document shows another firm, Winter Construction, scored better than Parrish on pricing, the McConnells said.

“Based on the documents provided to us, CSD has not conducted a competitive request for full, itemized pricing to ensure it is receiving the best value,” the McConnells wrote.

The McConnells called on the district to pause the project.

While the district has said the project is about equity and closing achievement gaps, residents of the historic Beacon Hill community said the project itself raises other equity concerns.

Decatur Day

Doris Sims Johnson and her family lived on Elizabeth Street in the Beacon Hill neighborhood in the 1960s and 70s. Johnson is one of the intervenors challenging the bond for the learning center.

The Beacon Hill community in Decatur was where freed slaves began to settle. The square mile area was the site of a thriving African-American community of homes, businesses, churches and schools. In the early 20th century, the neighborhood became known as Beacon Hill, according to the city website.

The city of Decatur’s Beacon Municipal Center, at West Trinity Place and Electric Avenue, was where the Herring Street School, Beacon Elementary and Trinity High School once stood. But the city’s “urban renewal” projects displaced the historically Black community.

“There’s no trace of it and very little is recorded in the history books here in Decatur, or in Georgia or anywhere,” Johnson said.

For about 40 years, families that once lived in Beacon Hill have celebrated Decatur Day, an annual reunion and celebration of the history and legacy of Black people in the city.

“Decatur Day was started as a way of celebrating all of the Black people who lived here. But even though we were dispersed and had distance between us, we still had a time to come together and reminisce,” Johnson said. “It was a family reunion, and it still is.”

The celebration started at McKoy Park and moved to the CSD-owned property on West Trinity Place and Electric Avenue in 2023. For some, this location holds deep significance — they grew up in the public housing that once stood on this very ground.

Johnson said that when she and the other organizers moved the annual event to this property, they were told it wouldn’t be developed for about a decade, so they were shocked to learn construction could start soon.

“It’s sacred. When we came here for Decatur Day in 2023, it was the greatest feeling,” Johnson said. “It was like, your connection with the land is the celebration and your reason for being here.”

The Decatur Day organizers learned that others had concerns about CSD’s plans and formed the Beacon Hill Grassroots Coalition. They said the learning center is being rushed.

“If everything's been approved and it's their land, they can do what they want to do,” Johnson said. “But maybe, if they heard from concerned citizens, it might slow or pause the thing, and hopefully we'd have them rethink it and do something else.”

Dean Hesse contributed reporting to this story.

.png)